The first wave of COVID-19 sent shockwaves through global economies. Once the haze began to lift, pressure started to mount on the UK government to commit to a green economic recovery. The world had changed almost overnight, but with it had come an opportunity to steer away from business as usual.

For the UK to reach its net zero target by 2050, significant progress will need to be made on a wider scale. It is not enough to encourage more household recycling or ban plastic bags, though these initiatives have an important part to play.

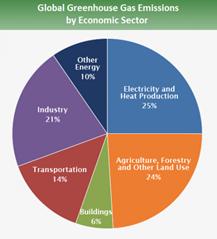

Big thinking is needed. While decarbonising electricity and transport have been central focuses of research and investment, agriculture is a huge emitter and poses one of the biggest challenges; however, it is not insurmountable.

Some innovative solutions show promising results, warranting further investigation.

Dietary changes and feed additives for ruminants

It might sound like an artificial additive, but fumaric acid is in fact an organic compound naturally present in all organisms and has been considered an acceptable feed additive for animals since 1967.

Research has found that when fumaric acid is included in feed, there is a significant reduction in methane production – up to 70% for lambs and sheep and 32% for goats.

This is not the only alternative diet that might positively impact our ruminal friends’ methane emissions. The local breed of sheep that live on the island of North Ronaldsay in the Orkneys have adapted to a life on the beach, primarily consuming seaweed because the high copper levels in the surrounding grass could be fatal. The seaweed controls the bacteria in their stomach, minimising the need for belching. The same positive effect has been found for cows. When just 1% of the seaweed Asparagopsis taxiformis is used as an additive in feed for dairy cows, methane is reduced by up to 67%. The seaweed further helps farmers economise on cow feed as reducing methane production also reduces energy demand in their bodies.

Land use

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to global food production, causing rising temperatures, droughts, and soil erosion to name a few. There is a very real future threat of food shortages without action.

One solution to this looming crisis is vertical farms. Not only can they produce more food than traditional farming, vertical farms use a fraction of the land and water consumed by their traditional counterparts. Furthermore, when grown in a vertical farm, a typically low yielding crop such as wheat can increase yields over 600 times.

One solution to this looming crisis is vertical farms. Not only can they produce more food than traditional farming, vertical farms use a fraction of the land and water consumed by their traditional counterparts. Furthermore, when grown in a vertical farm, a typically low yielding crop such as wheat can increase yields over 600 times.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have created a unique opportunity to scale vertical farms. A greater number of multi-storey buildings could remain vacant as a consequence of the surge in home working. Yet vertical farms are by no means a perfect solution, as artificial lighting and climate control require a lot of energy. However, using renewable energy sources as well as placing farms in strategic locations could overcome some of these concerns.

Where outdoor crops are concerned, basalt rock dust may provide some benefits both as a fertiliser and a means of carbon capture. When added to soils of cereal crops, basalt dust has been shown to increase yields by as much as 20% and absorb CO2 at a rate of two to four tons per hectare, four times more than untreated soil, over one to five years after a single application.

Additionally, global cropland-sparing has the potential to decrease the land needed to grow crops without affecting yields. This is the practice where instead of expanding to new land, crops are grown where they are already most productive and return the best yields, thus allowing for some land currently used for agriculture to be spared. Saving virgin forest and other previously unconverted land from farming is becoming imperative to avoid mass extinctions driven by habitat loss. Global cooperation would be necessary to achieve something of this magnitude, but were it to be successful, a substantial proportion of land could be rewilded.

Where next?

While none of these initiatives provide the answer on their own, they show that there are a multitude of achievable solutions to the climate crisis within the agricultural sector. In addition, encouraging changes to human diets by shifting away from mammal meat and toward avian meat and especially plant-based foods would help.

The UK is currently at a crossroads. It can either continue on the old path or forge a new one that is not only climate friendly but economically beneficial. Policies that seek to encourage economic growth through green initiatives can not only create new jobs but provide an environmental blueprint for other countries to follow.

One thing COVID has shown is how quickly policies can be implemented in response to a crisis. As we look towards a post-COVID future, will the same urgent response be given to the climate emergency?

Angela Wenham, Centre Manager, Climate Econometrics, Nuffield College

David Hendry, Co-Director, Climate Econometrics, Nuffield College