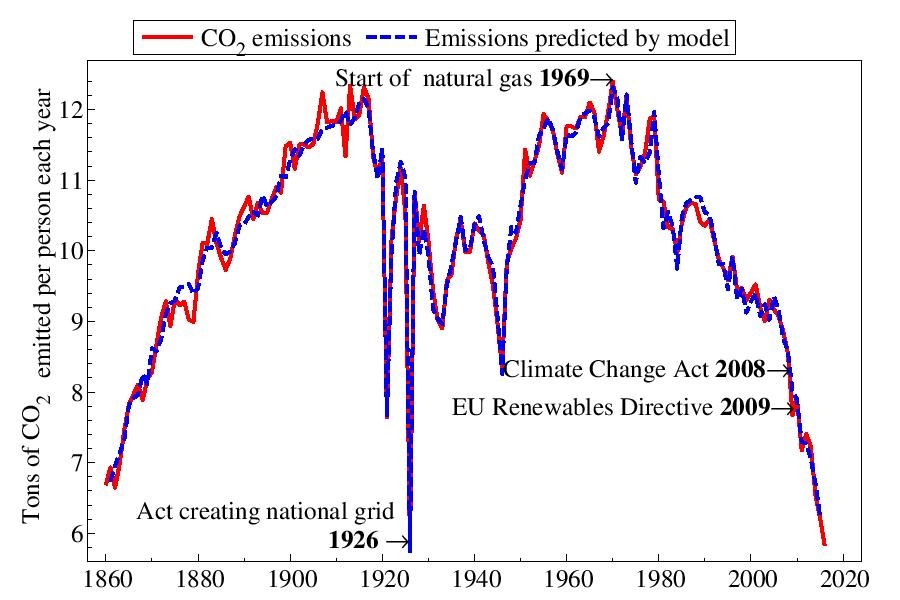

Taking root in the UK, the Industrial Revolution has since spread to various parts of the world, bringing with it technological advancement and wealth. While the benefits of industrialisation have been literally life changing, so too have been the negatives. UK emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), the most significant greenhouse gas causing our planet’s climate to change, exploded, going from around 6.5 tons per capita in 1860 to nearly double those levels at different stages over the following century, owing to increased use of coal and later oil.

Then something started to shift and CO2 per capita emissions in the UK began to steadily decline, leading to per capita emissions being lower today than 1860 levels. While there have been sharp intermittent drops in CO2 emissions due to events such as general strikes before this time, the recent trend suggests, since then, something different is happening.

This is where econometrics comes in as an investigative tool. Political and economic events are drivers of change; some obvious at the time and others more subtle. Econometric models, which are statistical tools that aim to approximate the processes that generate the data, must take these events into account in order to better understand whether a particular action or policy has had a significant effect.

To determine what could be driving down CO2 emissions in the UK in recent decades, our very own David Hendry uses the saturation methods he developed to investigate what might be causing this decline. Saturation refers to a technique, where all potential variables, i.e. different possible determinants of CO2 emissions, are considered and the model throws out what is unimportant in a fashion that mimics recent developments in machine-learning. This allows for the data to tell its story, without relying on preconceived, external ideas of the researcher being forced upon it.

So what does it tell us about UK per capita CO2 emissions? Using these methods, David identifies three major policy interventions that have had an impact: an Act of Parliament in 1926 that created the UK’s nationwide electricity grid leading to a substantial increase in energy efficiency; the start of the switch from coal to natural gas in 1969 where the costs of conversion of equipment were funded; and the combination of the UK’s Climate Change Act (CCA) in 2008 with the EU’s renewable directive of 2009. What is different about the two recent policies is their legal commitment to reducing emissions. The CCA requires the UK to reduce emissions by 80% below 1990 baseline levels, while the EU renewable directive requires 20% of energy consumed to be from renewable sources by 2020.

David finds that these two most recent policies have played a role in sounding the death knell for the UK coal industry, and have been instrumental in the decline of emissions in recent years. In May 2019, UK electricity ran for two weeks without coal for the first time in over a century and plans are currently in place to shut down the remaining 5 coal-powered electricity plants by 2025.

Change has not always been easy and there is an ongoing debate about how to address local losses that might occur from policy interventions. The risk of inaction when it comes to reducing harmful CO2 emissions is, however, much greater, not only to those communities but to society as a whole, as a wide body of research, including by Climate Econometrics’ Felix Pretis, Luke Jackson and Moritz Schwarz, shows.

There is much more to be done but David’s findings show how policy can be a powerful tool to bring about change. These findings also help policy makers to better understand what works and what does not, paving the way for more effective future climate policy. This is going to be necessary to achieve the government’s recent ambitious 2050 net zero target.

On the issue of climate, it is time to be politically bold. The example of the UK shows that well designed policies can have a significant impact. The question is, will future policy makers be bold enough to make these tough decisions?

Photo by Markus Spiske

Angela Wenham, Centre Manager Climate Econometrics, Nuffield College

David Hendry, Director Climate Econometrics, Nuffield College